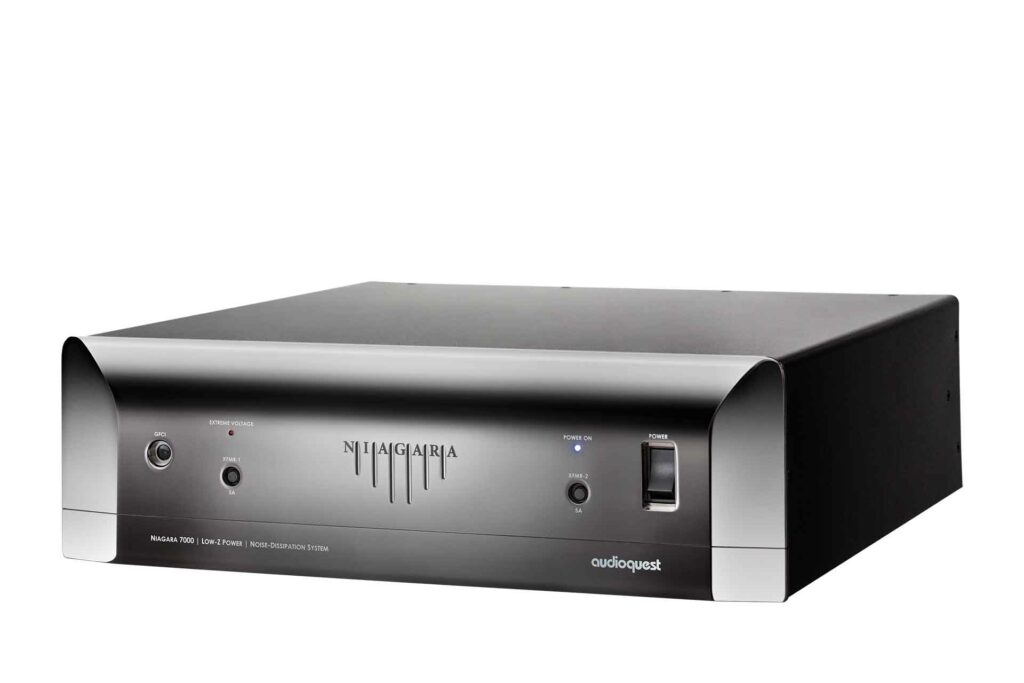

Before leaving for the 2025 Capital Audiofest (read Jerry Del Colliano’s 15 Thoughts article here)in Rockville, MD, I took the time, as is my custom, to completely power down my entire audio system. I also took the extra precaution of unplugging the entire system from the AC power supply. I use an AudioQuest Niagara 7000 Power Purifier (read review here) with overload protection, but I still decided to unplug it to cut power to my entire audio system for added safety. About 15 years ago, a lightning strike caused a voltage surge in an Esoteric stereo power amplifier I was using at the time. The unfortunate result was a non-functioning amplifier. After sending the amp back to the Esoteric service center in California, I learned the bad news. Both main circuit boards were fried and needed to be replaced. Oh, and let’s not forget the best part – the cost of the repair was just over $3,500. So, now, when I will be out of town for several days, I take the precaution of removing my system completely from the grid – thus avoiding any nasty surprises. Of course, weather issues can and do come up at a moment’s notice. A severe storm can occur whether I’m at home or out shopping. But by and large, I try to prevent any unwelcome surprises, having previously gone through one.

After coming back from the Capital Audiofest, I naturally felt like listening to music. Like so many others, I wanted to compare my system to what I had heard at the show. Or at least what I vaguely remembered hearing at the show. My power amp, the T+A A3000HV (read review here), has a myriad of protection circuits and operational indicators. Two are of note. One is a downward-pointing blue triangle indicating the unit has not yet reached thermal stability. The other is a hourglass-shaped icon indicating the amp is now operating at the optimum temperature. The A3000HV even has circuits designed to keep the unit at the ideal temperature. What I heard horrified me as I waited for the blue triangle to be replaced by that nice hourglass, and for my sonics to sound normal.

Is Audiophile System Warmup Real or Imagined?

This is one of the many topics about which audiophiles love to disagree. One perspective suggests that system warmup is primarily the result of the equipment sounding different from its usual state, leading to the perception of altered sonic characteristics. In other words, it is not better or worse, just different, and our ear/brain process will easily recognize “different.”

What I heard was certainly different. After powering up my system, the sonic presentation was different to the point of being terrible. I had little to no imaging on the right side. Dynamics? Almost none. The music, what there was of it, sounded as if a veil had been spread over the entire soundstage. Now, I was basically prepared for this, as I have heard it before. This is a normal occurrence when my system has been without any electrical power for days or even weeks. There was one new element this time, however. In addition to no imaging on the right side, the right speaker had a faint 60 Hz hum. Oh, boy. This sounds really great! Different? Yes. Far worse than normal? Absolutely.

After about 15 minutes, the blue triangle was replaced by my familiar white hourglass. The 60 Hz hum had disappeared and sounds from the far right of my listening room were becoming more noticeable. Dynamics were returning and music in general was sounding more normal. After 30 to 45 minutes, things really began to sound very familiar. And, after about 90 minutes, I was happily reveling in the magnificent sound my audio system normally creates.

Call it system warmup or whatever you choose. Call the before and after “different,” if you so choose. I’ll call the playback at less than the optimum operating temperature far worse-sounding than the version with my white hourglass. Sarcasm aside, for a short time, my system sounded terrible. And this brings me, finally, to my first reason to leave an audio system constantly powered up – to negate the warmup, or whatever anyone wants to call it, and presumed sonic degradation a less-than-thermal stability status renders. I have a limited amount of time to listen to music and I would rather not spend much of it waiting on amps, preamps, DACs, phonostages or anything else to sound their best. I want my best presentation immediately, not some time in the future. Sit down, press play and hear excellence is my goal. So, powered on around the clock works for me.

How Various Component Designs Handle Being Constantly Powered On …

If audio components sound better after a warmup period, what happens if they remain powered on all the time, 24/7? This is, of course, system-dependent. My system is powered up continuously and I have not encountered any issues as a result of this practice. My amplifier is Class-AB, where constant power is not a significant problem. My other electronics also have no problem being on all the time. My phonostage, for instance, is essentially designed to be powered on all the time. So, about the only notable issue I encounter is the power bill. We’ll get to that in a minute.

Leaving Tubed Equipment On All the Time Can Be Hazardous

Needless to say, SET (single-ended triode) and pentode tubed components can and should be turned off when not in use. For one, powering them on all the time will burn the tubes out much faster than turning them off when not playing music. Considering how challenging it can be for some analog enthusiasts to find replacement tubes, it’s logical to ensure their tubes have a long lifespan. Secondly, and let’s briefly circle back to the power bill, leaving tubed gear on all the time will noticeably increase how much you will spend on electricity. And lastly, tubes, by their very operational nature, create heat. Quite a lot of heat, in fact. In the summer months, tubes running around the clock may easily make the audio room too hot to enjoy the primary reason for being there in the first place – listening to music. Tubes, therefore, should be turned off when the music room is not in use.

Solid State Audiophile Equipment Is More Forgiving on Being Powered Up – Sort Of …

As previously mentioned, my reference stereo amplifier is solid state Class-A/B. It operates in full Class-A for about the first 40 watts and then switches over to Class-B. When at rest, or when no music is being played, the current draw is minimal. Leaving my Class-A/B amplifier on full time poses no significant drawback.

Full Class-A solid state amplifiers (and also Class-A tubed versions) are different. Class-A amplifiers are basically never off. When a music signal is presented to the input stage of a Class-A amplifier, the signal is not yet at speaker level. The output transistors are always powered on at full 100 percent power, even when no music is present. As such, the audio signal from input to output operates in a very linear fashion, has very low distortion and a simple signal path. The end result is that Class-A amplification is usually regarded as the best-sounding of all the amplifier classes. The downside should be obvious. This characteristic of the input remaining faithful to the output does render amazing sonics, but the amp is essentially running at full speed all the time. Here again, heat and the power bill are preeminently affected. And, if also left on all the time, depending on the design, the amplifier or other component may wear out prematurely. While it is a personal preference, it is always recommended to turn full Class-A components off when not operational. Some Class-A amps have a bias feature to throttle back the operation of the amp when not in use. If the amplifier is so equipped, the user may then choose a range of bias levels. Probably most common is something like 10 percent, 50 percent, or 100 percent of Class-A operation. Having this flexibility makes a full Class-A amplifier more user-friendly, thus significantly reducing the power consumption and heat.

What About Class-D and Gallium Nitride (GaN) Amplifiers?

Gallium Nitride is a hybrid of a Class-D, or switching, amplifier. Very simply put, in Class-D amplification, the incoming waveform is converted to a series of on/off pulses, or a switching signal. This switching of the signal is extremely fast. This typically results in a very clean, very low-distortion signal delivered to the output stage. These devices also operate at, depending on the design, somewhere near the 90 to 95 percent efficiency range. By comparison, full Class-A amplifier achieves roughly 25 percent efficiency, with around 75 percent of the total energy lost as heat. Likewise, GaN components are typically small, lightweight, and create almost no heat of any kind. And they provide this, in most cases, for an attractive purchase price. Leave them on all the time? Aside from electrical storms, leaving a Class-D or a GaN amplifier in a constant on position is a pretty safe bet. But because of their operational design, there really is little to no downside in turning them off when not in use.

What About the Power Consumption of a Continued Power-On State?

About 12 years ago, several years before moving into my current home, I performed an experiment. I wanted to try to ascertain how much extra I was spending to keep my system powered on all the time. To be honest, I wasn’t really concerned about the power bill. I was merely curious to see what I was spending.

I took the previous 12 months of power bills and added them up to get an average utility cost. At the beginning of a billing cycle, I left the system powered on for the entire month. When the bill for the powered-on month arrived, I compared it to my 12-month average. The next month, and before the weather changed enough to skew my results, I powered off the system when I was not playing any music. When I received that month’s bill, it was about $25 less than my 12-month average, and also lower than the previous month’s powered-on bill. I pondered this for about five minutes and quickly determined I was not going to change from leaving my system on all the time. For one thing, I do believe in warmup and I didn’t then or now want to be saddled by inferior sonics while waiting on thermal stability. Two, the extra $25 on the power bill doesn’t bother me. I’ll suffer the extra expense and learn to live with the disappointment. And of course, I also realize this is my opinion, and not everyone will feel the same. I encourage those who are interested to conduct their own experiments to see what powering their systems actually costs.

How Do Capacitors Figure Into This Question?

A capacitor, by and large, is an energy storage device. Energy is stored in two metal plates separated by an insulator. When power is applied, the capacitor charges to full capacity. When the power is turned off, the capacitor discharges completely. A capacitor’s main function is to smooth out the power coming from the power supply. It does this by stabilizing and filling in the dips and peaks of the voltage from the power supply, thus creating a very clean and stable DC current. Of course, the role of a capacitor is immeasurably more complex than outlined here. Virtually every audio component uses a capacitor of some type in some way. Without them, our audio systems would be vastly different. Here’s the rub. Capacitors have a service life. They can only be charged (when power is applied) and discharged (when power is terminated) just so many times. Once this threshold has been reached, the capacitor will begin to fail and whatever the component may be will eventually stop working. Operationally, leaving a component powered on all the time keeps the capacitors charged all the time. Not turning them off theoretically extends their lifespan and, consequently, the life of the component. Realistically, most capacitors are designed to work for a long time, so how quickly they may fail, or if they fail at all, is not a measurable, consistent condition. Call it provisional, depending on the capacitor design and how often it is charged and discharged. I once had an integrated amplifier last for about 20 years before the caps started creating problems. I knew then the jig was up and I replaced the component. Most of today’s audiophile equipment, it should be noted, is designed to last for many years of continued enjoyment. So, an individual’s possibility of capacitor failure may never materialize. Bottom line: if you want to basically eliminate the uncertain possibility of capacitor failure due to powering on and off, leave the system powered on. If this issue is of concern, and powering on and off is the path chosen, there is a potential risk of early component failure. Although such failure cannot be assured, it should be regarded as a possible outcome. In this, it is user’s choice.

Final Thoughts On Leaving an Audiophile System On or Off …

One of the things I like best about the audiophile hobby is the variety of choices we have. Think about it. We can choose from the big ones – digital or analog and tubes or solid state. We have a wide variety of speakers from which to choose. We can go with separate components or something more aligned with an all-in-one setup. We can even spend as little as $1,000 on an audiophile system or, with available resources, several million dollars. All of this can be classified as audiophile. And whadda-ya-know, we can also decide to leave our systems on all the time or not.

This is obviously a matter of personal preference. I am quite confident audio enthusiasts will have very determined opinions both for and against a system powered on all the time. And guess what? Everyone is correct! Leaving a full Class-A tubed system on all the time may not be the smartest thing to do, but if it works for an individual listener, then it makes perfect sense – at least to the individual who is doing so.

Ultimately, what we are all after is to make our system sound as amazing as possible. We may take wildly different paths in this effort. Some will be more avant-garde than others. But I tend to believe in the “whatever works” rule. So, should you keep your system on or turn it off? Very simply put, that’s your decision.

Great article Paul!

I absolutely hear a difference with my CH Precision amplifier as it warms up. When it gets to 49C things get magical, takes about an hour and a half to get there. I still typically turn it off when I go to sleep and back on in the morning. I did not hear much difference in the Michi S5 while I was reviewing it. My JC1’s sounded better when warmed up too.

I also unplug everything when I go out of town or when bad weather is expected.

Thanks Jim, glad you enjoyed the article!

In my experience, equipment warm up is real, and not just your ears getting used to the sound, or a change in sound, or whatever. My system sounds better after it’s been on for an hour or two. I have (and have had) guitar amps where the effect is unquestionable.

When I worked for Harry Pearson he would leave everything on all the time. I never got to see one of his electric bills but with running multiple systems with tube gear, I can only imagine the sticker shock.

Hey Frank! Thanks for your input! I can only imagine what HP’s power bill must have been. As for me, the audio system utility cost pales in comparison to the combination of HVAC/natural gas costs required to heat and cool this big house and keep the lights on!